Back Poisson's Equation Recall the Newton's law of universal gravitation:

F = − G M m r 2 r ^ , \boldsymbol{F} = - \frac{G M m}{r^2} \boldsymbol{\hat{r}}, F = − r 2 GM m r ^ , where G G G M M M m m m r ^ \boldsymbol{\hat{r}} r ^ M M M m m m

F = − M m r 2 r ^ , F = M m r 2 . \begin{align*} \boldsymbol{F} &= - \frac{M m}{r^2} \boldsymbol{\hat{r}}, \\ F &= \frac{M m}{r^2}. \end{align*} F F = − r 2 M m r ^ , = r 2 M m . By F = m a \boldsymbol{F} = m \boldsymbol{a} F = m a g \boldsymbol{g} g

g = − M r 2 r ^ , g = M r 2 . \begin{align*} \boldsymbol{g} &= - \frac{M}{r^2} \boldsymbol{\hat{r}}, \\ g &= \frac{M}{r^2}. \end{align*} g g = − r 2 M r ^ , = r 2 M . The gravitational force is conservative:

∮ C F ⋅ d s = 0 , \oint_C \boldsymbol{F} \cdot d\boldsymbol{s} = 0, ∮ C F ⋅ d s = 0 , meaning the work is independent on the path taken and depends only on the initial and end point.

The potential energy is defined as the work done to move an object of mass m m m r r r

W g = ∫ F ⋅ d r = − ∫ ∞ r F d r = M m ∫ ∞ r − 1 r 2 = M m lim n → ∞ [ 1 r ] n r = M m r . \begin{align*} W_g &= \int \boldsymbol{F} \cdot d\boldsymbol{r} \\ &= - \int_{\infty}^r F\ dr \\ &= M m \int_{\infty}^r -\frac{1}{r^2} \\ &= M m \lim_{n \to \infty} \left[\frac{1}{r}\right]_n^r \\ &= \frac{M m}{r}. \end{align*} W g = ∫ F ⋅ d r = − ∫ ∞ r F d r = M m ∫ ∞ r − r 2 1 = M m n → ∞ lim [ r 1 ] n r = r M m . And the external work W e W_e W e

W e = − W = − M m r . W_e = - W = - \frac{M m}{r}. W e = − W = − r M m . The potential is equal to:

ϕ = W e m = − M r . \phi = \frac{W_e}{m} = -\frac{M}{r}. ϕ = m W e = − r M . The negative gradient of the potential is the gravitational acceleration:

g = − ∇ ϕ . \boldsymbol{g} = -\nabla \phi. g = − ∇ ϕ . The flux of the gravitational field

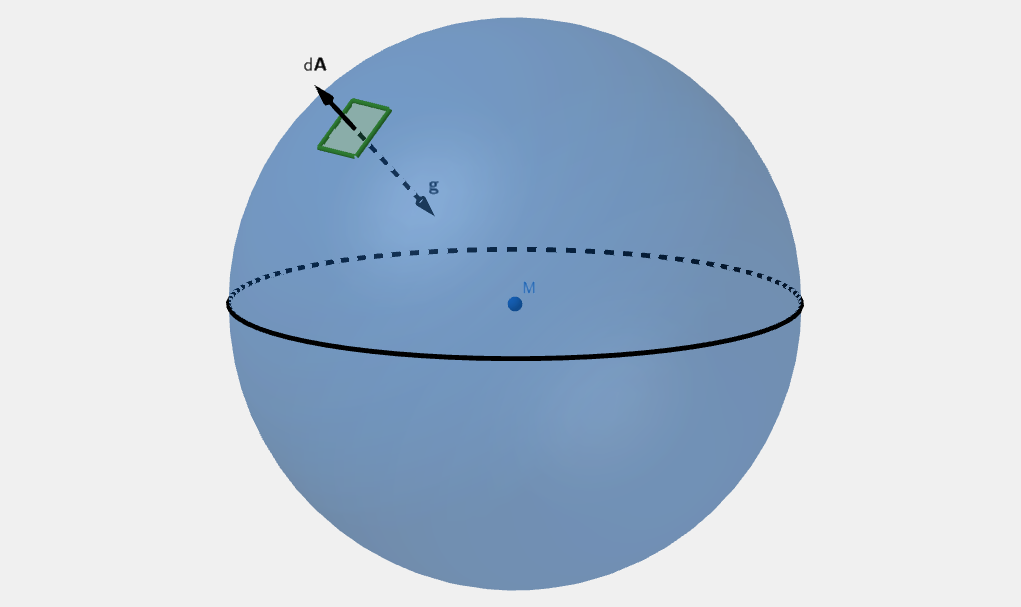

∯ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = − 4 π M . \oiint_{\partial V} \boldsymbol{g} \cdot d\boldsymbol{A} = - 4 \pi M. ∬ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = − 4 π M . For sphere, this would be:

∯ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = − ∯ ∂ V g d A = − g A = − M r 2 4 π r 2 = − 4 π M , \begin{align*} \oiint_{\partial V} \boldsymbol{g} \cdot d\boldsymbol{A} &= - \oiint_{\partial V} g\ dA \\ &= - g A \\ &= - \frac{M}{r^2} 4 \pi r^2 \\ &= - 4 \pi M, \end{align*} ∬ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = − ∬ ∂ V g d A = − g A = − r 2 M 4 π r 2 = − 4 π M , where M M M ∂ V \partial V ∂ V ∂ V \partial V ∂ V V V V

By the divergence theorem:

∯ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = ∭ V ( ∇ ⋅ g ) d V = − 4 π M , ∭ V ( ∇ ⋅ g ) d V = ∭ V − 4 π ρ d V , ∇ ⋅ g = − 4 π ρ . \begin{align*} \oiint_{\partial V} \boldsymbol{g} \cdot d\boldsymbol{A} = \iiint_V (\nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{g})\ dV &= - 4 \pi M, \\ \iiint_V (\nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{g})\ dV &= \iiint_V - 4 \pi \rho \ dV, \\ \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{g} &= - 4 \pi \rho. \end{align*} ∬ ∂ V g ⋅ d A = ∭ V ( ∇ ⋅ g ) d V ∭ V ( ∇ ⋅ g ) d V ∇ ⋅ g = − 4 π M , = ∭ V − 4 π ρ d V , = − 4 π ρ . Recall that gravitational acceleration is the negative gradient of the potential:

g = − ∇ ϕ . \boldsymbol{g} = -\nabla \phi. g = − ∇ ϕ . If we substitute this into Gauss's law, we obtain Poisson's equation:

∇ ⋅ g = − 4 π ρ , ∇ ⋅ ( − ∇ ϕ ) = − 4 π ρ , ∇ 2 ϕ = 4 π ρ . \begin{align*} \nabla \cdot \boldsymbol{g} &= - 4 \pi \rho, \\ \nabla \cdot (- \nabla \phi) &= - 4 \pi \rho, \\ \nabla^2 \phi &= 4 \pi \rho. \end{align*} ∇ ⋅ g ∇ ⋅ ( − ∇ ϕ ) ∇ 2 ϕ = − 4 π ρ , = − 4 π ρ , = 4 π ρ .